How may technology be conducive to human flourishing? If the pace of technological advancement continues unabated, how can there be pause for wise reflection? We must always be conscious of such questions and not necessarily expect progress to be positive. For technology is a potent example of materialism – it leads to more possessions, in terms of physical objects, but also in terms of mental objects demanding our time and attention.

Yet the way of contentment is often said as “less is more.” In the 17th century, Simon de la Loubère, the French envoy of King Louis XIV to Siam, remarked on the material simplicity of the Siamese he encountered. He considered the society very primitive (for instance, the printing press had yet to arrive), yet he found that they generally had a greater sense of well-being than Europeans. In his account, Du Royaume de Siam1, he opens Chapter II: On the Homes of the Siamese, and the Architecture of Public Buildings with

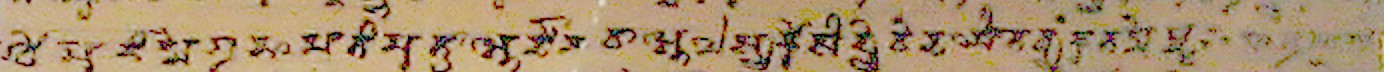

If the Siamese are simple in their habits, they are no less so in their accommodation, their furniture, and in their food: rich in a general poverty, because they know how to content themselves with few things.

Why is that? They followed a way of life that understands that external trappings are not what really matters, but what happens inside, the cultivation of the mind/heart. This is a message still being echoed today. When interviewed for an item on religion and smartphones, Dr. Piya Tan, Lay Buddhist Minister in Singapore, advised that apps are “pushing the senses outwards, gathering information outwards … meditation turns senses inwards … [to] see what’s going on in the mind.” In his view we don’t need apps because “apps would be quite a distraction.”2

This challenge may thus be characterised as developing technology that helps to deepen and enrich, so that the mind gains internal assurance. We may go so far as saying that with regard to this criterion this service may be deemed a success if its users find that using it enables them to be increasingly able to live without it, to become mentally and emotionally more independent.

This is, of course, just one approach to evaluation, but it’s the kind of approach that we argue is necessary for us to wisely control technology rather than find ourselves being controlled by technology. There is also growing evidence from recent research in neuroscience that a key requirement for our retaining control is to ensure that we allow ourselves sufficient space to cultivate the finer qualities of being human. Work by Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and others has indicated that the way technologies are used does not provide enough time to reflect and offer compassion, admiration and other noble human virtues.3Interviewed for a university news item she states:

“For some kinds of thought, especially moral decision-making about other people’s social and psychological situations, we need to allow for adequate time and reflection“4

Read more … about cultural variation.

Notes

1 Simon de la Loubère, Du Royaume de Siam, Vol I, available online through Google Books: http://books.google.com/books?id=wbQUAAAAQAAJ

2 Carmen Roberts. Smartphones make religion mobile, BBC Click, 2 September 2011 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/click_online/9578162.stm

3 Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Andrea McColla, Hanna Damasioa, and Antonio Damasioa, Neural Correlates of Admiration and Compassion, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(19):8021-6, published online: 20 April 2009.

4 Carl Marziali. Nobler Instincts Take Time. USC News Science/Technology 14 April 2009. https://news.usc.edu/29206/Nobler-Instincts-Take-Time/