The “mind of goodwill” is a translation of the Pali phrase metta cittena –citta means “mind” and “metta” means “goodwill” or “friendliness”. This brings us to the question of what we mean by “friendship”.

It may sound obvious to ask this question given the ubiquity of “friend” advertised at the heart of many SNS today. However, in spite of all the communication channels, are we getting closer to deeper understanding of each other? It is evident that in many environments, especially those in a busy urban setting, can lead quickly to stark isolation1. There is no doubt that SNS is affecting the fabric of society, yet it is not a question that has received a great deal of sustained scrutiny.

It’s no wonder then that SNS have generally persisted with deploying a single connection type, labelling it ‘friend’, an atomistic view that effectively dilutes relationships to a lowest common denominator, enriched only in part by privacy options. In this scenario, describing relationships is reduced merely to ‘friends’, ‘friends of friends,’ and so on, together with possessions and interests held in common. By putting all ‘friends’ in the same basket also raises problems of trust with various risks; if you are not careful, people you think are friends may be selling your information on to undesirables. Workarounds such as opening multiple accounts both go against the intentions of the system developers and create unnecessary dichotomies because, for example, work connections can become close friends.

We address these limitations by considering a Buddhist view, because it is exceedingly nuanced in its notion of ‘friend’ and offers substantial relevant guidance. According to this view, the right kind of friendship is seen as essential to well-being in society and is a matter that requires active and conscientious cultivation. The Buddha used the term kalyāṇamittatā, which means “association with good friends or good friendship,” and defined it thus in respect of the conditions of welfare:

“Herein, Vyagghapajja, in whatsoever village or market town a householder dwells, he associates, converses, engages in discussions with householders or householders’ sons, whether young and highly cultured or old and highly cultured, full of faith (saddha), full of virtue (sīla), full of charity (cāga), full of wisdom (pañña). He acts in accordance with the faith of the faithful, with the virtue of the virtuous, with the charity of the charitable, with the wisdom of the wise.”

Vyagghapajja Sutta, A iv 281, A translation is available by Ven. Narada Thera from Access to Insight:

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an08/an08.054.nara.html

Also available part of a compendium:

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/narada/wheel014.html

It is thus a mode of wholesome activity that spans body, speech and mind through a process consisting of four basic criteria that should be actively cultivated. Kalyāṇamittatā is listed in the sutta as one of four sampadā (blessed accomplishments) that brings worldly happiness and exhibits human flourishing.

Distinguishing between Feigned and True Friendship

It is now an opportune moment to introduce our friend, Sigala, a householder, who was advised by the Buddha on cultivating skilful relationships, as recorded in the Sigalovāda Sutta2. In this sutta the importance of kalyāṇamittatā is emphasized through a detailed explication of how to discern between fake and real friends. In each case there are four kinds to watch out for. These are listed below side by side in the following tables: on the left is the case of fake friendship, or “a foe in the guise of a friend,” whilst on the right is the true friend, “a warm-hearted friend.”

| Fake

Friend (1) One who appropriates |

True

Friend (1) A helpmate |

| (i) appropriates their friend’s wealth | (i) guards the heedless |

| (ii) gives little and asks much | (ii) protects the wealth of the heedless |

| (iii) does his/her duty out of fear | (iii) becomes a refuge when you are in danger |

| (iv) associates for their own advantage. | (iv) when there are commitments they provides you with double the supply needed. |

| Fake Friend

(2) One who renders lip-service |

True Friend

(2) One who is the same in happiness and sorrow |

| (i) makes friendly profession as regards the past | (i) reveals his secrets |

| (ii) makes friendly profession as regards the future | (ii) conceals one’s own secrets |

| (iii) tries to gain one’s favour by empty words | (iii) in misfortune s/he does not forsake one |

| (iv) when opportunity for service has arisen, he/she expresses his/her inability. | (iv) sacrifices even his/her life for one’s sake. |

| Fake

Friend (3) One who flatters |

True Friend

(3) One who gives good counsel |

| (i) approves of their friend’s evil deeds | (i) restrains one from doing evil |

| (ii) disapproves of their friend’s good deeds | (ii) encourages one to do good |

| (iii) praises him/her in his presence | (iii) informs one of what is unknown to oneself |

| (iv) speaks ill of them in their absence. | (iv) points out the path to heaven. |

| Fake Friend

(4) One who brings ruin |

True Friend

(4) One who sympathises |

| (i) a companion in indulging in intoxicants that cause infatuation and heedlessness | (i) does not rejoice in one’s misfortune |

| (ii) a companion in sauntering in streets at unseemly hours | (ii) rejoices in one’s prosperity |

| (iii) a companion in frequenting theatrical shows | (iii) restrains others speaking ill of oneself |

| (iv) a companion in indulging in gambling which causes heedlessness. | (iv) praises those who speak well of oneself. |

It is this kind of friendship that is in mind in the design of sustainable SNS – the development of virtue sustains human relationships, particularly in difficult times; the practice of charity cultivates exchange, but through virtue and wisdom the practice does not waste people’s time or other resources.

The phrase ‘good-will’ is particularly significant, being a translation of mettā, more commonly rendered as ‘loving kindness,’ and is pure and refined in nature: “Metta succeeds when it loves, and it fails when it degenerates into worldly affection”3. Such affection is said to be rooted in tanhā-pema or rāga, a selfish love or passion, attached to sense pleasure, as distinct from the non-attached mettā. Such attachments, which are typical of much SNS use, lead to frequent disappointment, only transient happiness and ultimately to lack of fulfillment and to reduced well-being. In fact, the Visuddhimagga4, a popular commentary on some early Buddhist texts, goes so far as to describe rāga as the near enemy of mettā5; it is thus an obstacle to building social welfare.

On this basis we can proceed to develop a suitable model for

relationships.

Notes

1 Some services offer company for a fee, raising the question, Is a rented friend a real friend? Claire Prentice, BBC News, 5 October 2010 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-11465260

2 DN 31 PTS: D iii

180 Sigalovada Sutta: The Discourse to

Sigala: The Layperson’s Code of Discipline

translated from the Pali by Narada Thera.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.31.0.nara.html

3 Buddharakkhita, Acharya. 1989. Metta: The Philosophy and Practice of Universal Love, WH 365,6. Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy. Available online at: http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/buddharakkhita/wheel365.html

4 Buddhagosa, Visuddhimagga – The Path of Purification, Nanamoli trans., Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy. http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nanamoli/PathofPurification2011.pdf

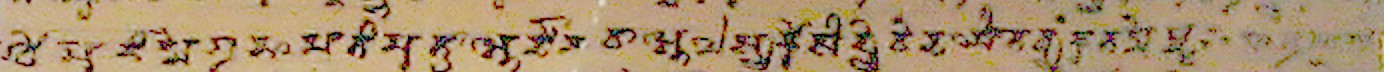

5 “Ekekassa

cettha āsannadūravasena dve dve paccatthikā.

Mettābrahmavihārassa hi samīpacāro viya purisassa

sapatto guṇadassanasabhāgatāya rāgo

āsannapaccatthiko “[Vsm. IX.98]

http://tipitaka.org/romn/cscd/e0101n.mul9.xml