We need to take care about how we mediate relationships online. The way we propose to do this is to understand elementary human processes and then proceed to anchor our designs on nurturing more meaningful friendship.

Individual Actions and their collective significance

It is a common characteristic of online services that usage is determined as much by peer behaviour as by individual choice. Accordingly social networking services emphasize doing things together collectively –hence the term community platform. Accordingly, the functionality of systems may be oriented towards real-time content syndication, and sharing information to multiple audiences. Whilst this may be very convenient in a group context for achieving certain tasks, especially those requiring instant cooperation, a predominance of this usage has serious implications in terms of individual identity, autonomy, and the nature of communication.

If one’s activity on a system is habitually sending status updates in undirected fashion then over time this may diminish one’s ability in more directed communication. Such communication is essential to the nurturing of relationships, fundamentally how we relate to each other 1-1, as human beings. That’s why we should first consider the individual, their motives and behaviour, and then examine in depth the nature of relationships between individuals (or what are technically termed ties).

Yet the analysis of ties has tended to dwell on mere connectivity, i.e. whether or not there is some kind of connection, with little discussion about the nature of relationships in qualitative human (and humane) terms. Academic analysis is largely in terms of the current mainstream SNS with much attention given to social graphs (the graph of online connections between people). This is a term that gained popularity from the notion of six degrees of separation between any two people on Earth1. Some of this is likely due to the discipline of sociology having moved out from the small-scale personal origins of its pioneers such as Émile Durkheim into the large-scale macro impersonal sphere characterised by numbers and statistics2. A few ethnographers have come in to fill some gaps, but there is little evidence of their having more than decorative influence on either the academic literature or on SNS.

This is especially the case in regard to well-being: plenty has been written, but this emphasis on macro methods has led to most of the analysis constructed to yield statistically significant findings. This orientation particularly affects the crucial subjective dimensions, which have been heavily dependent upon surveys with question designed to elicit self-perceptions of happiness to fit prescribed categories. The context is further constrained because the analysis often hinges on the notion of social capital, whose various definitions are typically expressed in terms of possession of resources3.

This methodology is deeply problematic because – as already indicated at the outset –deeper levels of happiness and contentment are not based on material possessions, so social capital should be regarded as just one factor. Yet such sentiments seem not to feature highly in Western indices of well-being and in consequence evaluations have been more concerned with the question of building the system right than building the right system. Given the huge social impact of SNS, we really should concern ourselves more with the issue of the right system. We argue that this is a question fundamentally rooted in ethical issues and addressing such issues gives rise to a different complexion in the analyses. The field is currently slim, but there is research in philosophy that has sought to apply virtue ethics in assessing the ethical impact of SNS technologies – see especially work by Vallor4. We propose a similar approach, albeit rooting our ethical analysis not in Western Philosophy, but in the teachings of the Buddha and particularly what they say about friendship.

Next … defining relationships

Notes

1 See e.g. Brian

Hayes. Graph Theory in Practice (Part 1),

Computing Science: American Scientist, Volume 88,

Number 1, January–February, 2000, pp. 9–13, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i27857951

(article available elsewhere as PDF).

Hayes mentions with scepticism an oft-cited claim via

a play that the earliest notion of ‘Six Degrees’ was

mentioned in Marconi’s Nobel prize winning speech.

Indeed that seems to have been a perpetuated myth

since the speech provides something different: a

calculation of network coverage for fixed wireless

transmitters.

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1909/marconi-lecture.html

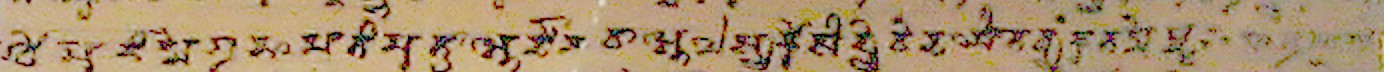

2 For example, Pierre

Bourdieu (Le capital social: notes

provisoires, Actes de la Recherche en Sciences

Sociales, Vol. 31, Jan. 1980, pp. 2-3) defined it as:

l’ensemble des ressources actuelles ou

potentielles qui sont liées à la possession d’un

réseau durable de relations plus ou moins

institutionnalisées d’interconnaissance et

d’interreconnaissance

which Portes translates as: the aggregate of the

actual or potential resources which are linked to

possession of a durable network of more or less

institutionalized relationships of mutual

acquaintance or recognition.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1980_num_31_1_2069

3 See e.g. Portes, A. 1998. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24, 1-24

4 Vallor, Shannon. Social networking technology and the virtues, Ethics and Information Technology, Volume 12 Issue 2, June 2010, Kluwer Academic Publishers Hingham, MA, USA.